Political Awareness | In Parliament | The Workplace | Why South Australia?

The Aboriginal Voice | Cultural Diversity

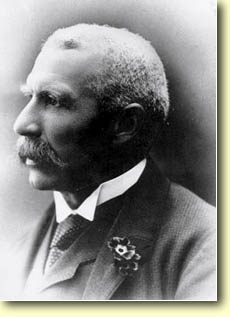

Sir

Edward Stirling

Sir

Edward Stirling

It was not only women who were actively involved in the campaign for women's suffrage—many men were also key players. Foremost among these was Dr (later Sir) Edward Stirling, first President of the Women's Suffrage League, from 1888 to 1892, and who introduced the first women's suffrage legislation in the South Australian Parliament. Photograph from the Mortlock Library of South Australiana pictorial collection (B11259).

Helen Jones in In her own name: a history of women in South Australia from 1836, revised edition (Adelaide, Wakefield Press, 1994), and reprinted here with her kind permission, describes Dr Stirling thus:

"He was born at Strathalbyn in September 1848, the son of Harriet and Edward Stirling who was a pastoralist. In Adelaide he was educated at St Peter's College and in England at Trinity College, Cambridge where he gained degrees in arts, medicine and science. He had a deep interest in scientific matters, and on returning to live in Adelaide in 1881 became a consultant at the Adelaide hospital and the first lecturer and later professor of physiology at the University of Adelaide. In 1884 he also became director of the South Australian Museum, which was to be his life's interest, and for three years was a member for North Adelaide in the House of Assembly. In 1886 he was foundation president of the State Children's Council.

Stirling was a man of many talents, enormous energy and concern not only for science but for people. Widely read, he was interested in public affairs both in England, where women's suffrage was debated among his friends, and in South Australia. He corresponded with William Woodall, leader of women's suffrage moves in the House of Commons. The motive for his women's suffrage Parliamentary initiatives lay in his character and background; as a scientist he saw no reason why women should be cut off from public responsibilities. As a husband and father of daughters he had first hand knowledge of their capabilities, which he also observed in female students at the Advanced School for Girls and at the University of Adelaide. Liberal in his politics, he was prepared to stand up for principles and to work for his beliefs.

Stirling was knighted in 1917 and died at his Mount Lofty home in 1919."

Helen Jones earlier sets the scene for the community's increasing support for the concept of women's suffrage in Chapter 4 on 'The suffragists'.

"The lives of people who worked for women's suffrage disclose something of the campaign itself, and of the nature of South Australian society. The suffragists were both women and men: rich, poor and comfortably middling in income, middle aged, young and elderly. Most who were actively involved lived in or near Adelaide, and many were church members, mainly of Nonconformist denominations. For some, but by no means all, concerns about the effect of alcohol had led them to join temperance societies or the Women's Christian Temperance Union, which favoured prohibition. Some were members of trade unions and some were members of Parliament. They had in common a single aim: to achieve the Parliamentary vote for women.

Women's suffrage supporters carried on a campaign to win the vote over almost six and a half years. Many people met and worked together during that time; new members joined, but at the heart of the campaign stood a group whose sustained activities kept the Women's Suffrage League before the public. At each of the League's meetings in Adelaide many of the same faces could be seen either in the Victoria Hall (in the YMCA building on the corner of Gawler Place and Grenfell Street), at the Albert Hall (in the German Club in Pirie Street, east of Gawler Place), or in other central locations. The League's affairs remained newsworthy throughout the campaign; press reports of meetings and of individuals' comments and speeches are invaluable in view of the apparent loss of the League's records.

Among the suffragists some were clearly leaders; seven women who were in the forefront are Mary Lee, Mary Colton, Elizabeth Nicholls, Catherine Helen Spence, Rosetta Birks, Serena Lake and Augusta Zadow. Mary Lee was apparently present at all meetings; her judgement of others is valuable. Among those she acknowledged she first named Lady Colton 'who has so heroically stood by them (the members of the League) through all difficulties and discouragements'.

In her estimation there were four men whose names should live on South Australian history's 'brightest page' for their part in gaining the suffrage: they were Dr Edward Stirling, Mr Robert Caldwell MHA, the Hon. Dr Sylvanus Magarey and the Reverend J C Kirby. She summed them up like this: Stirling she said was 'the Vice-President, whose masterly speech in our Parliament of 1886 (sic) first gave Australian birth to the aspiration'. Caldwell was the one who 'so courageously championed their cause through two consecutive session (of Parliament)', while Magarey 'has never failed whenever and wherever he could help us'. Last, 'but not least' was Kirby, 'whose chivalrous loyalty and eloquent advocacy of the cause since its inception would be but beggared by any praise of mine'. These men were eminent in the cause but by no means the only ones who had influence.

Certain organisations, in addition to individuals, played a part in the suffrage campaign. At the centre of the campaign was the Women's Suffrage League whose work was crucial. The Women's Christian Temperance Union gave strong backing from 1889, and in turn it had the support of the men's Temperance Alliance on suffrage affairs. The Working Women's Trades Union and the United Trades and Labor Council were committed to women's suffrage and their members cooperated in supporting the Women's Suffrage League. The United Labor Party too had a loose working relationship with the League. Some influential non-conformist denominations-the Methodists, Baptists and Congregationalists-supported the League's principles.

Youth groups, including some church organisations, literary societies and young men's societies all took an interest in the question and debated and discussed women's suffrage. Beyond these organisations, and sometimes within them were a number of prominent individual clergymen and members of Parliament. The allegiances of individuals and the role of various organisations emerge to some extent in the brief biographies below and in the next chapter. There was no publicly organised opposition to women's suffrage, although there were frequent scattered attacks and a few adverse Parliamentary petitions. Within Parliament, debates gave ample opportunity for opponents to elaborate their views."

You may wish also to see the complete story of Votes for women.

| Copyright and this website | Disclaimer | Privacy | Feedback | Accessibility | FOI This page last updated on Friday 11 April, 2014 14:46

|

State Library of South Australia |